The Secularization of Hindu Dance and Art Forms and the role of Hindu Philanthropy

Manish Maheshwari

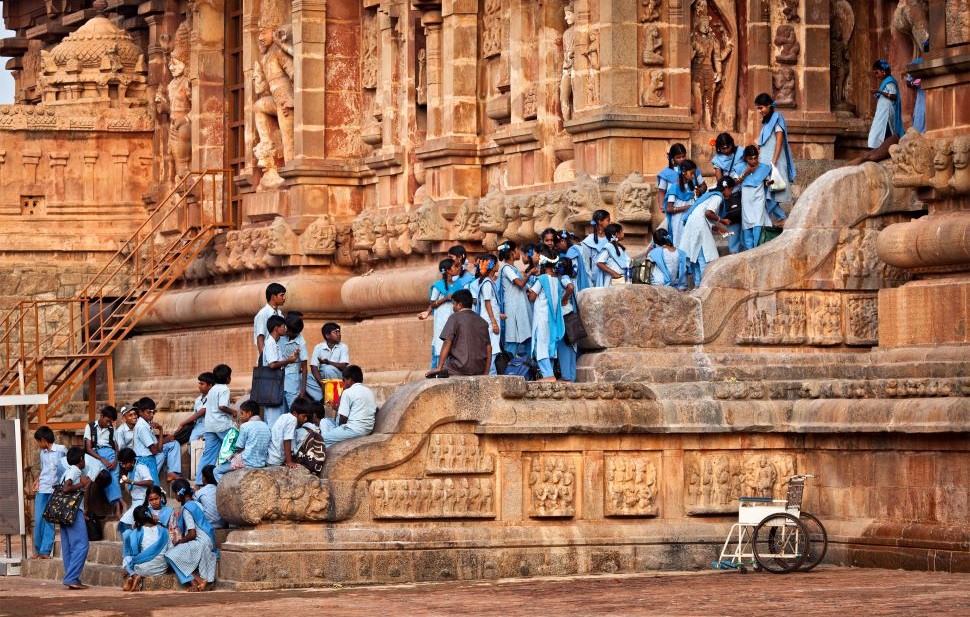

This essay is an attempt to understand how Hindu devotional dance and art forms that was, for a thousand years, nurtured in the great temples as an offering to the Gods and nourished by the prolific corpus of Pauranic stories, deals with the changed circumstances of the modern world.

Devotion

While on a pilgrimage to Puri Jagannath Rath yatra earlier this year, I got a chance to talk with one of the finest Odissi dancers about her art and what it means to her. During the conversation, as the majestic Jagannath Rath approached us, she exclaimed in a moment of joy, “I dance for him (Jagannatha).” A bit later, we had the immense fortune to hold the rope and pull Lord Jagannatha’s Ratha. After the exhilaration of the moment had passed away into a cherished memory, we continued the conversation. She said that dance is a vehicle for expressing her love for her God and her Guru, and for reaching the state of transcendence (I paraphrase). She said that, even if one has the best technique in the world, if the practice is not infused with devotion, then “What is the point of dance?” (her words). When I enquired if her students felt the same way, she replied in the negative, saying the current generation, in general, does not look at dance as a form of devotion. Slightly apologetically, she said that her students think that she is “old school” (her words).

The challenge of modernity

Later, speaking to some of the younger Odissi dancers, I found that many of them were interested in exploring secular themes—climate change came up a few times in our conversations. One of the other Odissi Gurus I met with was interested in experimenting with faster rhythms and contemporary themes to make Odissi “more appealing” to younger audiences and to attract new enthusiasts.

What I am trying to grasp is how a Hindu devotional dance form that was, for a thousand years, nurtured in the great temples as an offering to the Gods and nourished by the prolific corpus of Pauranic stories, deals with the changed circumstances of the modern world, where artists have to fend for themselves for their livelihood. Devotion becomes difficult when modern artists have to worry about ticket sales for their performance, the need to spend countless hours trying to make that perfect Instagram-worthy post, and the constant jostling for government and corporate sponsorship.

The Hindu dancers also have to take into account that the world is no longer as religious as it was even just one generation ago. The audience might not be aware of the rich corpus of Pauranic stories that the dancers are trying to convey through their dance. Moreover, with the advent of western education and the epistemological commitments it brings, it is often the case that the audiences and the sponsors tend to look at dance as a form of desacralized cultural entertainment performed for stage commitments rather than an elevated form of devotion—which remains the prime purpose of Hindu dance according to the Hindu texts.

This shift in perspective is exacerbated by the fact that the major patron of Hindu dance is, by far, the secular Indian government. The government bureaucrats, in general, are agnostic with regard to the content of the dance, as long as the form of the dance is maintained. Therefore, in our example, an Odissi dancer has as much chance of getting funding from the government for a secular theme as for a devotional theme, provided the dance is Odissi, which is classified by the Indian government as an “Indian Classical Dance”.

Some questions

Of course, we cannot take dance forms back to the “pristineness” of pre-capitalistic forms of patronage but it is deeply unsatisfying to see our sacral tradition being left to the whims of our secular government, to the vagaries of capitalism, and to the latest fads of the age. If we allow these forces to go unchecked in determining the direction of our ancient music, art and dance forms, our devotional dances will be completely overwhelmed by the zeitgeist. Now, I am not arguing that dances on secular themes should not be choreographed at all, but the question is at what cost to the tradition? Can the tradition maintain its sacredness if profane themes become a major part of the tradition? Currently, this is not a major issue, as the memories and lineage of old gurus is still alive and this keeps a check on the tradition going in a radically different direction. For our dance forms, we still haven’t reached the stage that Yoga finds itself in, where “post-lineage” yoga is the new topic of the season, at least on the media-academia circuit—but eventually such an ideology will sweep into our other religious art forms as well.

Another question is why should tradition adhere to its sacredness? If the secular state and dance academies look at Odissi as a form of cultural entertainment rather than a Hindu dance form, then why not follow their lead? If a patron enjoys the Odissi dance form, he should not care if the dance is about the divine love of Krishna and Radha or LGBTQ love. Moreover, secular themes will attract a broader range of audiences which will lead to increased popularity of Odissi and wider patronage for Odissi dancers. Even better, Odissi combined with, say, a Bollywood dance form might lead to a new genre of dance and more YouTube views. The possibilities seem endless. At least this seems to be the trend in Bharatanatyam.

The need to maintain the sacredness of Hindu art and dance forms

I felt uneasy writing the paragraph above. There is something about the secularization of our religious art forms that makes me uncomfortable. When I try to pin down the source of my discomfort, some answers come immediately to mind, the primary one being the sense of wanting to stay true to the tradition, so that the tradition can be preserved and passed on to the next generation. The foundational text of Hindu dance, Natyashastra, states that dance was created by Lord Brahma to wean people away from excessive attachment to the material world. Taking certain aspects from each of the four Vedas, Lord Brahma created the Natyashastra, a Veda of Hindu dance, so that people can enjoy the material world through the medium of dance in a manner that is both a delight to the senses and also spiritually elevating.

Religious dance forms are unique to the Hindu tradition, where they are considered to be one of the supreme forms of devotion and sadhana. The religious themes of our dance forms, chosen from our epics and Puranas, allows both the performer and the audience to transcend the senses through the means of senses. It is a time-space where the relentless secularization and rationalization of all forms of our modern life are put on hold, and the senses are allowed to explore those realms of thoughts and feelings which are inaccessible to us in our day-to-day lives.

In modern times, there is a tendency to think of Hinduism as confined to worship at public temples, or private spaces in the home, to the exclusion of other forms of devotion such as music, dance, meditation, yoga, satsang, karma yoga, and so on. This radically truncates the immense diversity of ways that we approach the divine in the Hindu tradition. The constriction of our religious universe and imagination into certain specific ways of worship leads to the relentless secularization of all our other modes of worship—be that yoga, meditation, art, or dance forms.

Maintaining boundaries: Tradition as a guide

Hindu dance must be, first and foremost, seen as a form of devotion rather than cultural entertainment. It is one of the means of showcasing the moral, ethical and spiritual teachings of the Hindu tradition. Indian traditional dance, as I have pointed out earlier, has been nourished on an inexhaustible corpus of Pauranic and epic stories, a veritable treasure trove of materials for our dance choreographers to draw their material from. In order to preserve the roots from which that nourishment flows, strict boundaries should be maintained between traditional dance and other secularized forms of dance, including Bollywood.

People might say, in objection to this view that Hindu dances and art forms should adhere to their Hindu roots, “Our art forms have through centuries continuously changed and adapted to the altering circumstances and we must also do the same.” Or, more radically, some might say, “Our art forms should be allowed to chart their own course unimpeded by the mores of the tradition.”

The latter argument can be dismissed right away. Tradition is a crutch, a guidance and a source of stability—the basis on which any art form charts its future course. There is no question of being unimpeded by tradition. The art form is already embedded in the tradition and any deviation from the tradition will still look up to the tradition as its source of inspiration and a marker to compare itself against.

The first objection about the historic changes in the art form and the need to adapt to more contemporary times is more valid. However, change cannot be an ad-hoc process based on the whims of sponsors or the latest fashions of the time. That is not how the tradition has renewed itself. Historically, change was always dealt with and navigated by the elite practitioners of the tradition who were deeply embedded in it, and not some outsider to the tradition with reformist zeal. It is the enlightened guru who innovates upon the tradition based on the hermeneutic impulse from the tradition itself, whether it is the innovation in yoga practices by the great Tirumalai Krishnamachariar, or the innovation in Odissi dance by the great Kelucharan Mohapatra.

But then the charge will be that the elites who are embedded in the tradition will, by definition, be conservative and loath to tamper with it. The response is that it is precisely because the elites were conservative that the tradition itself has survived and thrived for an astonishingly long period of time. If every generation had wanted to tamper with our art forms based on their whims or the latest fad, then there would have been no devotional art form or even the hoary guru-shisya parampara. It is the adherence to the parampara which maintains stability and the longevity of the art form. If the goal is to preserve, propagate and creatively renew the tradition, then being conservative is not necessarily a bad thing.

The role of patrons

There is another issue. If the elite of a tradition wants to radically alter it or take it in a different direction—say the Odissi dance legend, Sanjukta Panigarahi, choreographing an Odissi dance on Shakespeare’s Othello—I think this is where the role of patrons comes into the picture. The entire art form depends upon patronage—be it from the government, corporates, or individuals. It is the ideological motive of the patrons that determines, to a large extent, in which direction the tradition will veer. For example, up till a few decades ago, the astonishingly beautiful and complex dance form, Kudiyattam, was performed within temple premises and only a Hindu could witness it. However, due to external pressure, lack of patronage, and the financial emasculation of Hindu temples, the dance form moved out of the Hindu temples and is now regularly performed on the proscenium stage to international audiences. The more glaring example is Yoga, which emerged from the Shaiva tantra and was largely practised by Hindu ascetics and yogi householders but has now become a global phenomenon backed by the full might of capitalism. Due to the collapse of traditional sources of patronage—Hindu kings, temples, and devout merchants—the elite practitioners of the Hindu art form have had to increasingly look for other patrons for their livelihood. This process cannot but lead to Hindu art forms secularizing themselves in order to cater to newer audiences with different sensibilities.

Conclusion: Hindu philanthropy and its goals

While there is something to be said for the democratization or popularization of Hindu dance or other art forms, this must not come at the cost of radically altering the tradition away from its roots. The dance or art forms should be innovated upon on their own terms, foregrounding the tradition that has nurtured them, and not at the whims and fancies of market forces and the dominant ideologies of the day. A conscious effort has to be made to ensure that the funding of our art and dance forms is underpinned by certain values and philosophy—and this is where private Hindu philanthropy comes into the picture.

Hindu philanthropy as a term is still nebulous and, as far as I know, no philosophical articulation has managed to define what constitutes Hindu philanthropy in a way that has been done for Christian charity or Islamic zakat. As I have mentioned earlier, historically, patronage of Hindu art and dance forms was an important element of Hindu charity, however we may define it, but, due to the vagaries of time and change in our world-views, Hindu charity is no longer associated with such types of patronage. Patronage of such kind has been completely taken over by the government and, increasingly, by the business corporates. There is definitely a need for course correction but, even before such a process begins, there is a need to define the contours and goals of Hindu charity and demarcate it from other forms of charity. As a starting point, any modern concept of Hindu charity has to take inspiration from our vast literature on daan (charity) and a thorough historical survey is required to understand how the Hindu traditions were financed and supported both by the laity and the kings. Currently, we are in a situation where even our temple funds are directed to causes and activities that are not directly relevant to Hinduism. In our future articles, we will have a chance to further define and discuss the shape and direction of Hindu philanthropy.