Should the Indian State Manage Culture?–Part 1

Manish Maheshwari

This essay is the first in a series of essays consisting of some of my personal reflections gathered over many years of travelling and meeting stakeholders engaged in the preservation and promotion of our cultural heritage. These stakeholders are individual artists, performers, wealthy patrons, cultural enthusiasts, and most notably of all, politicians and government officials in the cultural ministry. The Indian Government, represented by these politicians and bureaucrats, is the largest patron, by far, of culture in India. Culture ministry budgets run into hundreds of crores, and this substantial sum is disseminated through various government-sponsored academies, museums, and cultural centres.

It is the last set of stakeholders, the politicians and bureaucrats, that I am most concerned about here. Through grants, sponsorships, and various funding programs under the cultural ministry, these government officials shape the cultural landscape of the country. Through the quirks of history, a modern non-religious homogenised bureaucratic organisation, largely meant to administer the finances and law and order in the country, has become the primary patron of India’s ancient and astonishingly diverse cultural heritage, most of which is steeped in the religious tradition of the land.

This wasn’t always the case. Historically, our culture and art forms were funded by devout kings, temples, merchants, and artisan groups. But, after the dissolution of the nominally independent kingdoms post-independence and the curbing of their privy purses by the modern Indian State, the ability of this hereditary aristocracy to fund culture declined dramatically. It is these small kingdoms, ruled by highly devout and cultured kings, that have historically patronised the art and culture of the land. However, at present, most of the old cultured aristocrats have converted their palaces into hotels to sustain themselves, and, in most cases, they are involved in bitter legal battles with the Government of India to salvage their land and property holdings from government takeover.

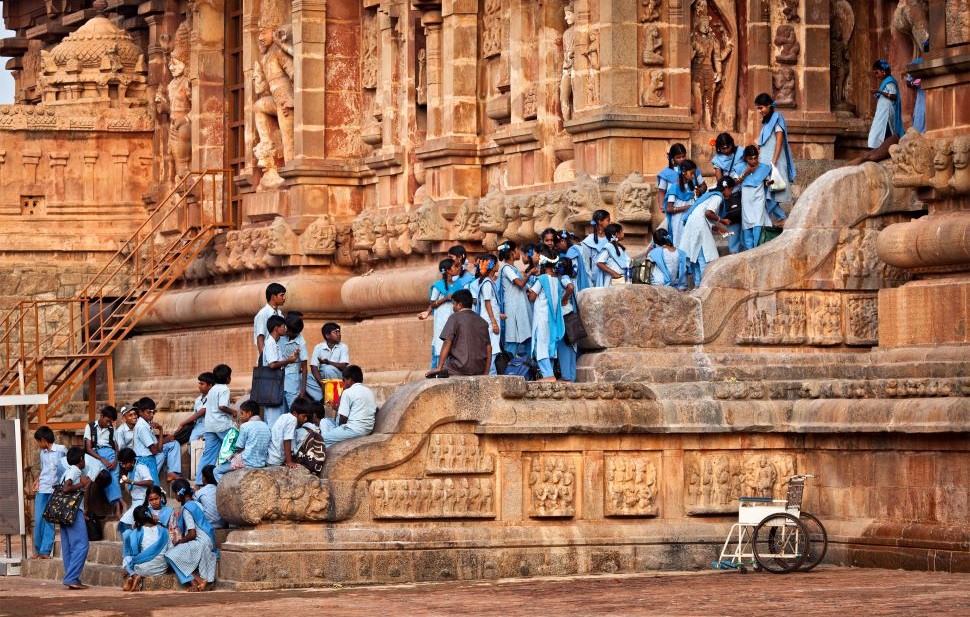

Further, the modern Indian State’s grip over large temples and their revenues dramatically curtailed the ability of these temples to freely sponsor art, music, and dance forms associated with the temples. Historically, most of our performative and visual traditions—be it music, dance, crafts, or paintings—were deeply embedded in the temple tradition of India, and the temples were the largest patrons of art forms. As I write today, no one really knows what happens to the vast riches of the Hindu temples under the vice-like control of the Indian State.

Further, the precipitous decline of artisan groups in this industrial age and the ruinous rate of taxation on wealthy individuals have ensured that they are no longer major patrons of India’s art and culture. Thus, the ancient sources of patronage that sustained Indian culture became toothless as India gained independence and modernised itself, and into this vacuum entered the giant colossus, the Indian State, which took it upon itself to be the legatee of millennia of vast patronage provided by the kings, temples, and merchants.

It is illumining to read some of the discussions, deliberations, and speeches of the office-bearers during the early years of the newly independent Indian State as it took on the responsibility of managing and funding India’s culture. One such speech is by Maulana Abdul Kalam Azad, the Union Education Minister, who, in his opening address at the inauguration of the Sangeet Natak Akademi in 1953, said:

“Tradition cannot be preserved but can only be created afresh. It will be the aim of this Akademi to preserve our traditions by offering them an institutional form…In a democratic regime, the arts can derive their sustenance only from the people, and the State, as the organised manifestation of people’s will, must, therefore, undertake…maintenance and development [of arts] as one of [its] first responsibilities.”

There is a lot to unpack in this small excerpt. Notice the Government wanting to “institutionalise” our tradition (and also notice the use of the singular term for tradition); notice this amorphous entity called the “people” to whom the culture belongs; notice the Government assigning itself the responsibility of the “maintenance and development” of India’s tradition and culture. In the next set of essays, we will examine all of these terms and ideas, but for now, I am interested in what the result is after 75 years of institutionalisation, government management, and the development of Indian culture. Has the modern Indian State been a worthy legatee of millennia of vast patronage provided by the kings, temples, and merchants?

One way to answer this question is to take an empirical route and do an analysis of all the Government’s cultural investments through its various institutions over the last 75 years. This has been done before to some extent, and it doesn’t present a pleasing picture. One only has to read the government-appointed High-Powered Committee (HPC) reports and the reports of the Parliamentary Standing Committee on Culture on the functioning of the Cultural Ministry and the institutions under its control to see how ill-equipped the Ministry of Culture has been to manage and promote the cultural heritage of this country.

Gleaning from the four reports over the last 70 years presented by the HPC, the last being in 2014, suggests issues such as perennial lack of funding, the appointment of politicians and journalists as chairpersons of various Akademis, antiquated systems, lack of specialised manpower in the Cultural Ministry, no long-term vision behind cultural funding, the debasement of cultural institutions as an arm of the Indian State and its ideology rather than independent organisations, the encroachment on the autonomy of the cultural institutions, the bickering over the Centre and State cultural institutions for funds and control, and many other such issues. In one of the revealing paragraphs of the 2014 HPC report,

“…is the State machinery able to appreciate the nuances of creativity, and to encourage, and harmonise, the many voices of human endeavor? The representatives of Government often believe that theirs is the power and the right to receive obeisance. On the other hand, our ambassadors of culture are sometimes so uncultured in their ways; some of them do not know the difference between self-actualisation and self-aggrandisement…How does one then find a balance, in practical ways, between benign patronage and excessive control, between creativity and accountability, between a stolid bureaucracy and cultural freedom?”

While the HPC reports correctly highlight the issues ailing the cultural ministry and its inadequacy in managing India’s vast cultural heritage, it mainly deals with administrative lacunae and lack of expertise. We are almost given a picture that once the cultural ministry is efficiently managed, there will be a grand revival of Indian cultural traditions. But one cannot escape the feeling that all such reports and recommendations are just that—an eye wash—a chimera that something is being done. Many such reports have been presented in the past, but as the reports themselves lament that nothing has been done with those recommendations, and there is no reason to believe that the future will be any different.

Undoubtedly, efficient and more enlightened administration of the cultural ministry will certainly help, and the very fact the cultural ministry is aware of this issue is salutary, yet one cannot escape the fact that the vested political interest and the Government’s need to use its cultural institutions as an arm of State ideology will hardly allow an independent flowering of India’s diverse cultural tradition. Further, the Culture Ministry, unlike the patrons of yore, will still be managed by career bureaucrats and politicians of the Indian State who are spectacularly ill-equipped to be the patrons of India’s astonishingly sophisticated and diverse cultural traditions. Culture is a specialised subject, and it requires years of training and reflection to understand the wide registers of Indian culture and its philosophical underpinnings. Instead, bureaucrats are transferred to the cultural ministry on a rotation basis and are given charge of managing such knowledge-sensitive divisions as manuscripts, museums, cultural mapping, etc.

It was sheer good luck that India found someone like Kapila Vatsayan who, due to her proximity to the Gandhi family, could skirt the entire bureaucracy and build a world-class cultural research organisation, IGNCA, with government money. But relying on such good luck is not a long-term strategy. Look what has happened to the IGNCA under the present dispensation.

Most of these issues are well known, and the reports themselves highlight it. As a legatee of India’s vast cultural heritage, the Indian State has not been able to live up to this great task of being the enlightened patron of Indian culture. Returning to the initial question—should the Indian State manage India’s cultural heritage?

The answer is NO.

This negative response is not solely because the Cultural Ministry is poorly managed; that would be an obvious and banal answer. There are deeper philosophical reasons why the modern Indian State should not oversee Indian culture. My contention is that the State is fundamentally opposed to the sources that animates the cultural tradition of this land. It has a deep animosity against the very people, the societal structure and the religious traditions in whose womb the culture of this land was born and nourished.

We will discuss this in detail in Part II of this essay series.